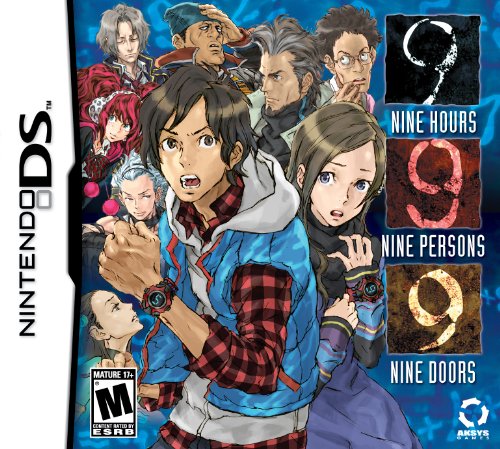

Nine Hours. Nine Persons. Nine Doors.

A survival horror visual novel, 999 is much more of a reading exercise with occasional puzzles thrown in than it is a game. This does nothing to dampen the experience, but it will be an obstacle for many. 999 has "cult†written all over it; those with the patience to see the nonary game through to completion several times are almost guaranteed to develop a certain fondness, if not love, for the Gigantic and at least some of its denizens.

Certainly, in my five days playing through the game to absolute completion, I came to think of my DS as the ship itself; few games have ever been quite so genuinely affecting as 999, nor quite so suited to the form despite their unorthodoxies.

999 begins opens with Junpei, an unassuming college graduate, waking up aboard a sinking ship with the number 5 on a device his wrist. He quickly remembers that Zero, a figure in a gas mask, drugged him and dragged him there, and soon meets eight other people who met the same fate. Notes in their pockets reveal that the nine of them have been selected to play the Nonary Game, and must progress through numbered doors until they locate the exit: door number nine. Failure to complete the game within nine hours will result in a sunken ship and presumable death by drowning; failure to abide by the rules of the game will result in bombs exploding from within their stomachs.

The Nonary Game is based upon mathematical equations, but Aksys has decided to be kind to innumerate people like me: for the most part, the dialogue discloses which combinations of characters can go through each door and the player merely has to choose which door is the right one for them. Story progression is periodically determined by Junpei choosing which door to go through and responding to prompts from the other players in the game. Progress through the ship is only in the player's control for the duration of the numbered rooms, a series of tap and examine puzzles of varying difficulty and intricacy. None of them are ever rendered insoluble, and clues are liberally sprinkled throughout.

The game's final puzzle is literally a game of life-and-death sudoku and, while that may be fun to some mindsets, I had absolutely no qualms in simply loading up a copy of the grid off the internet and tapping the results directly onto the screen. By that point 999 is definitely not about gameplay of any form, but simply about reaching the end of a story that you've been reading for hours, if not days; the dying hours of the game are so dialogue heavy that any input on the player's part feels like an intrusion and disruption of flow.

While the story and the multiple branches are undeniably the draw card of 999, the sheer weight of the dialogue and exposition runs counter to its essence. I would not have welcomed a real time limit of nine hours upon myself as the player (not that any of the puzzles are that difficult), but there is no real sense of urgency for these characters except in situations where they're convinced that they're going to blow up. Everything that they say is relatively interesting (although you wait to figure out why the characters are talking about their chosen subjects, many of which seem pretty out there), but everyone is rather too laid back about their possible impending doom.

I am certain that in the game's dying days, when there was less than an hour left until imminent doom, I spent more than an hour reading explanations of concepts both pertinent and tangential to the situation at hand. They were undeniably fascinating, but ran entirely counter to the thoughts that would have permeated my own mind in such a situation: "It's less than an hour until my stomach explodes, I need to get the hell out of here before my stomach explodes.â€

999 succeeds in that it asks me to consider how I would feel if some sort of crazed millionaire placed me in a game of death with an array of character types; it fails in that this level of consideration made me question the actions of almost everyone aboard the ship. Still, that tiny failure is insignificant in the face of the greater work that has been achieved in 999.

999 offers five endings, three of which result in multiple horrible deaths, and one that you have to secure to obtain the true ending. In the best case scenario, the game demands two full play throughs, but it does warrant all five (six if you insist on obtaining the pointless "dummy†ending).

The game is designed so that you have to take on each room so that you can completely discover each character's backstory, and you only get three rooms per play through. Even if you choose a path that you know will result in death, you'll get at least some interesting information out of it. This only holds true if you're able to care about the situation and the characters; if you didn't get something out of your first play through I can't imagine that repeatedly bludgeoning yourself with the game will improve the situation.

The idea of multiple play throughs may sound daunting, but Aksys saw fit to counter this by giving you the option to fast forward through any dialogue and text that you have encountered in previous runs. This serves the dual purpose of hastening a process that could grow very dull through repetition and emphasising the focus on new (and, by extension, exciting) developments.

I recommend looking at a spoiler free FAQ so that you can plan optimal ending acquisition; in this way, by my fifth and final play through I was taking on one room for the first time ever, and that room significantly changed the experience of the room taken thereafter.

The fact that you have to play through ending five to get the true ending seems nonsensical at first, and to be honest, it kind of still is in the final analysis – but the concept remains interesting, even as the game gets further away from its core of nine hours, nine persons, nine doors. Everything eventually makes sense, even as it doesn't really. A certain suspension of disbelief is required, but by that point you've bought so much that it's not too difficult to just go with the flow. The game has many key reveals, and the most outlandish are saved for the proverbial eleventh hour.

I may have made a mistake playing through the penultimate ending first, because this furbished me with a lot of information about certain characters and mysteries that are key to the game overall. At the same time, this ending was the second longest and second most intricate, and therefore made my bloody deaths in the others seem less anticlimactic because I knew I was working towards something. Still, I was being surprised up until the final announcement of "THE END†(at which point I said "ha!â€) and I don't regret any of the game.

Many complaints that can be levelled against the game are pretty subjective; I'm a pretty fast reader, and the player is drip-fed the text. Whether it's too slow is up to the individual player, but I found that the pace of delivery didn't annoy me – and the aforementioned fast forward feature is something of a godsend for replays. People enjoying the game will likely edit the text in their minds so that they don't notice some things are needlessly repeated by being phrased multiple times in marginally different ways, nor will they notice that words like "sickingly†aren't actually existent in any respectable dictionary.

The writing is not necessarily stilted, but sometimes it feels unnatural; the narrator is quick to judge Junpei if it becomes clear that he has said the wrong thing, and the visual aspect of the visual novel form is frequently ignored in favour of paragraphs of text, the sound of footsteps and motion lines manifesting on the screen. Given that we live in the internet age, it's not entirely surprising but it is disappointing to find that some of the dialogue is overtly memetic: who would have guessed that at least two games in the DS library would feature the line "Well, excuuuuuuuuse me, princess� Certainly not I. Fortunately, this does not happen often enough to detract from the game

A general consistency of characterisation is maintained, but it falls apart on one key character who can't seem to quite decide how they are feeling at any given time, their attitude varying wildly from room to room in one play through before finally settling on something satisfactory (gender pronoun eliminated to prevent spoilers, also to render sentences much more awkward). This character provides some of the game's most chilling moments, but at the same time it is hard to reconcile their actions in one timeline with the more socially acceptable version of the character presented in the true series of events. It's a trade off between satisfaction in something cool and chilling and the firm belief that [character] would never do that; on the whole I think that it works, for who knows what evil lurks in the pockets of jackets?

Ultimately, people will play 999 for the concept and the feel, not for the little gameplay that it offers. If you don't find yourself frustrated by the speed of the text, you will discover a genuinely immersive experience that manages to surprise until the very last. An intriguing idea eventually layers on intrigues that one never would have suspected were possible from the outset, and everything is oh so very neat. There is a faint ridiculousness about the project, but in this industry I think we're just about ready to accept that and run with everything that is thrown at us.

999 is the sort of game that will turn away many players before they've had the chance to have the hook inserted, but it has already worked up a dedicated (and deserved) cult following. I'm not strictly sure if I could play it again, at least not so intensely, but I got my money's worth … and I have been toying with the idea of having another date with an axe.

999 gets the Doenau Seal of Extreme Approval, and I'm certain that's the highest recommendation I'm authorised to provide.