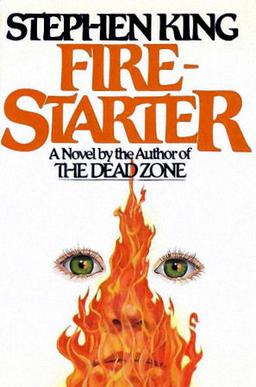

The Vietnam War, Watergate, the existence of Richard M. Nixon, the Cold War and basically anything overtly political in the wake of World War II bred a healthy distrust of the US Government. Whenever something even vaguely good or hopeful eventuated, like a fresh faced Kennedy with an impenetrably thick accent, it got shot down. It is through all of this that Stephen King brought us Firestarter at the turn of the eighties, just before Ronald Reagan came along to Make America Great Again for the first time, a legacy being paid for … with interest … in the modern era.

Firestarter is the sort of novel that, were it not presented in the traditional King "bestseller with depth†format, is both written and read under the safety of a tinfoil hat. In the world of Firestarter, and our own Keystone Earth, governments are capable of great evil. But in King's world, evil produces tangible results.

Charlie McGee is six years old. She's on the run from a government entity known as The Shop with her ailing father. And she can set things on fire with her mind.

In Firestarter, King does not bother with a preamble. He's right in it from the beginning: a father and daughter on the lam, the daughter trying her hardest not to do bad things, a man's shoes taking flame. The past is not prologue, but seamlessly interspersed with the main narrative flow: we learn why Andy and Charlie are fleeing as they are fleeing it, and when we're in one timeframe we never miss the other.

Firestarter marks another first for King: his first Native American villain in Rainbird. It is natural to view this character with suspicion, but apart from some racist language that Rainbird applies to himself, he is never characterised as the "noble savage†one might have feared from King. Rainbird's psychopathy and bizarre fixation on death are informed largely by his war experiences rather than being blamed specifically on his heritage, and none of his actions are stereotypical … or even sensical. As always, these matters of representation are best examined by someone closer to the themes, but on the Stephen King racism scale, Firestarter sits low.

Rainbird is a unique villain in the early days of King's catalogue in that he is written as if he were a paedophile, and he has to explain that this is not where his passions lie. This does not exonerate him, but rather adds an extra layer of creepiness and impropriety to a character who was already a remorseless killer. Rainbird is complex, but King never invites us to feel deeply for him. He stands in contrast to the only borderline-competent Shop administration and agents; ruthless, efficient, and single-minded in his goal. It's just an incredibly unwholesome goal, and the most legitimately disquieting

Despite protests to the contrary — that he just "wants to tell a story†— much of King's work is overtly political, and Firestarter is unavoidably so. You can't write a novel featuring illicit government psychic experimentation and a man ruined by Vietnam without a political thesis coming through, and if readers aren't able to see this not particularly subtle message because of the pyrokinetic bells and whistles, that's on them.

There are some things that a country just can't come back from. America never really got over Vietnam, they just papered over the cracks with a few more interminable and illegal wars. The prosperity gospel works for some, but for others it created a Hell on Earth. Firestarter is caught in the middle of an endless cycle, one that today can be read as quaintly optimistic. Published on the cusp of Reagan's reign, King had no idea what was yet to hit the United States.

Firestarter is a novel that captures many of the best elements of Stephen King: loving father and daughter dynamics, preternaturally intelligent children, bureaucratic incompetence and, of course, psychic powers. It has a taut structure, a stellar cast, and a suitably incendiary finale. Firestarter captures the paranoia thriller zeitgeist of the eighties, and stamps all over it with that indelible King magic.