In The Institute, we unlock the paradox of Stephen King: much of his best work is familiar and comfortable, echoing across the years, spanning decades. However, there is such a thing as too familiar: when King uses one his skeletons but forgets to put the muscle on the bones, the books suffer. The Institute is the ghost of a Stephen King novel: it has the spirit, but not the flesh. It's fine, but it's not much more than that.

Acting on a hunch, somewhat disgraced policeman Tim Jamieson arrives in the small town of DuPray and takes up a job as a night knocker. There we leave him and shift to Luke Ellis, a preternaturally intelligent child with latent telekinetic activity. Unfortunately a shadowy organisation known only as The Institute collects children like Luke, and he is placed in their system. Once on the inside, however, Luke wants out — and the Institute has provided Luke with exactly the right tools to achieve that goal.

The Institute begins with promise: a drifter shows up in a small town and settles himself in. But King forgets that we like to read about small towns and the people who populate them, and we leave them behind like so much table setting. When we eventually get back to them — their story not allowed to be told in tandem with Luke's until many hundreds of pages later — we don't get to know them. There is one character, Tim's love interest, whose only real characteristic is that she's not cut out for police work. That's it for the whole novel. As King settings go, DuPray isn't really a place so much as a staging ground, a cardboard film set with extras milling around and waiting for their squibs to go off.

So instead we have to rely on Luke, and he shows promise, along with his fellow victims in the grand conspiracy. The thing is that on the outside he is incredibly clever, has an eidetic memory, and can move pizza trays with his mind when he gets stressed; on the inside all of his smarts count for nothing, and he is flattened into just another kid. There's nothing exceptional about him and, unlike other King wunderkinds, none of these children can do anything much despite their ripeness for harvest.

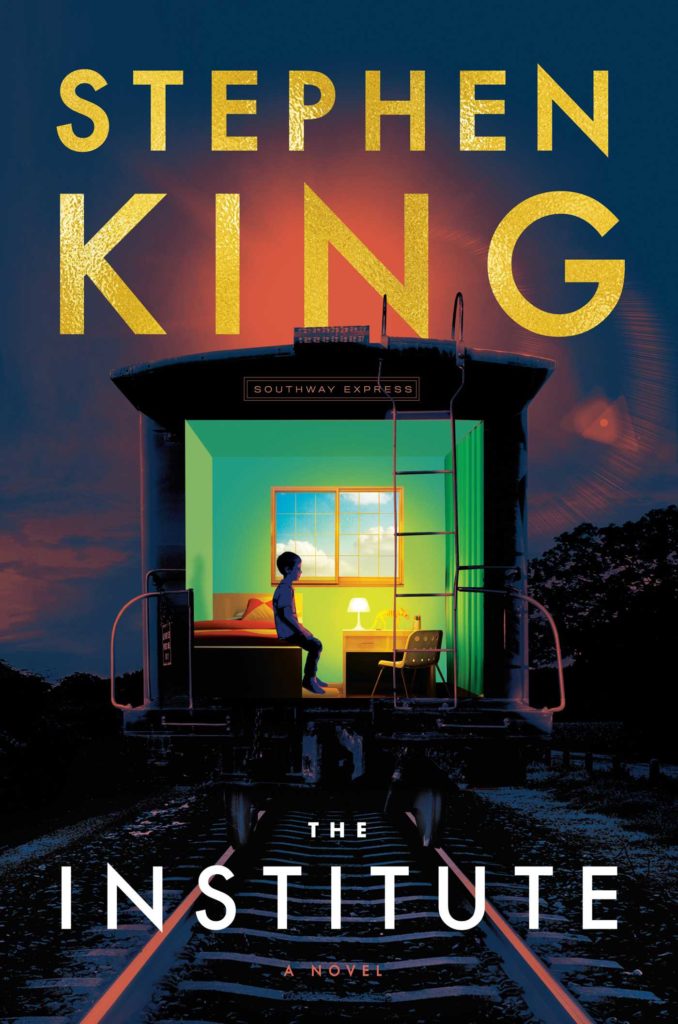

Yet the group of children together aren't without their charms, and the bond that they form is real. Their situation is static, however, much of the story is confined to the one location, and the screws who run the place are barely sketched in. The Institute itself sounds suspiciously like Firestarter's The Shop, but once we realise that it is most emphatically not tied in to Firestarter — or any other King novel save a name check that we get so often now that it's amazing that nothing has been done with that location in forty years — interest wanes. The Institute's US cover has one of the more arresting images in recent publishing history, but the contents never really live up to that one moment.

The Institute is a book in which one character says that polite society no longer allows people to be called morons; the same character will then go on to call a miscalculation on their part "maximo retardo†not once, but twice. King is a sentimental man, and The Institute was written for his grandchildren. Perhaps this is how they talk, but it is at least eleven years too late to be having a discussion about the dreaded "r wordâ€. It doesn't make Luke seem more endearing or give him the innocence of childhood: it smacks of a 72 year old man trying for a juvenile voice and failing in an embarrassing fashion. Given that King is famous for his empathy and understanding of the developing mind, and that The Institute is about children, it's a misstep. It may only show up twice, but it's enough to give The Institute a sour taste, emblematic of its general mishandling of character notes.

Still, it's not fair to say that The Institute is a failure on King's part: there are some intriguing revelations towards the end; not all of the character work is a bust; the climax returns King to his patented juggling of multiple character sets, some of which are quite affecting; and the whole generally holds together even when it doesn't soar.

The Institute has so many of the ingredients that normally constitute a premium Stephen King novel, but they fail to rise. If the reader were allowed to get more of a feel for DuPray and its people, then the two worlds might have meshed into a satisfying conclusion. There are elements that work, but more that fizzle. The Institute isn't a waste of time, but it's not King at the top of his game; the 2010s have not been unkind to the man, but this is a bit of a bummer to end the decade on.