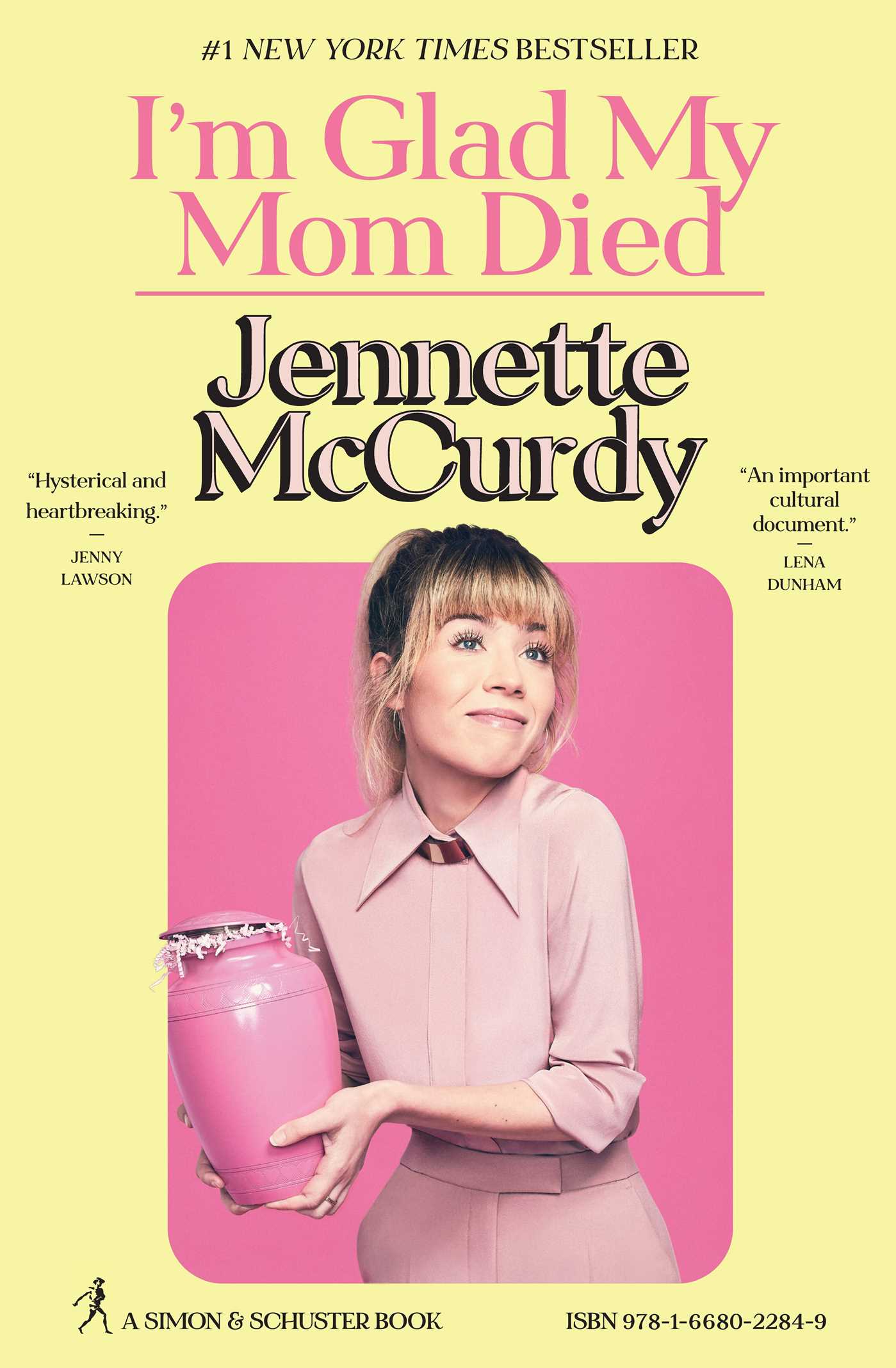

From the mid-noughts to the mid-tens, Jennette McCurdy played the breakout character in a Nickelodeon sitcom, which got her a degree of fame and fortune (allegedly garnished due to a bureaucratic failure). Then she kind of faded away. Her memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died, has generated a lot of buzz, which seems unusual to an outsider to the Nickelodeon ecosystem. iCarly was watched by millions, but as McCurdy herself says, it was the dead-end fame of child acting, an ecosystem that can be near impossible to escape.

Internationally, at least, it could be said that McCurdy is now more famous for this book than she ever was for iCarly or Sam & Cat. The 65 weeks on the New York Times hardcover best seller list certainly isn’t hurting her, but it’s also proof that her success isn’t entirely down to her notoriety: a combination of good publicity and a compelling story have allowed her to escape the walled garden of childhood fame for literary stardom and a potential new career.

I’m Glad My Mom Died is the true horror story of a girl who was dedicated to pleasing her mother at the cost of her own desire, who had to ride in the booster seat of her car at the age of 14 because her eating disorder was so pronounced, who suffered multiple indignities, who was likely repeatedly harassed by The Creator of her show (less disclosure here for legal reasons), and then developed a whole new set of problems after her mother died from the cancer that had been hanging over the family for two decades.

McCurdy seems open within the boundaries that she’s allowed. Famously she didn’t accept $300,000 from Nickelodeon to sign an NDA, so there’s a lot that she says that many others that she worked with might not necessarily have been able to – and, “coincidentally”, Dan Schneider’s career has been blown up since publication.

The most surprising element of I’m Glad My Mom Died is that McCurdy is able to be open about her jealousy of Ariana Grande and what she perceived as the preferential treatment Ari received on Sam & Cat (from the context clues provided here, it does seem like Ariana Grande had much freer rein). That seems to open her up to more hatred than anything else in this book. Contrast to the way she talks about Miranda Cosgrove as a very supportive friend, even after they drifted apart due to the passage of time. Grande is less a person than she is a distant figure of envy, but even that could be enough to set Stans off.

But of course you’re here for the Mom material, and McCurdy has that in spades. She’s dead, so she can’t sue. From the origins that McCurdy had, it’s somewhat amazing that she was able to be stage mommed so effectively: a homeschooled Mormon born into relative poverty, raised in a home so cluttered from hoarding that the children couldn’t access their bedrooms and had to sleep on gym mats, and with no real passion for acting beyond doing it because it makes her Mom happy. McCurdy is accurately able to paint this as horrific, because there is nothing calm or nurturing about it.

Things only improve marginally materially as McCurdy finds more success and books more jobs, and the degrees of control actually get worse. McCurdy is able to inject some levity into her account (which she narrates herself in audio form), but despite having money she never manages to make her existence fun. Even when she’s recording music in Nashville for a record deal that feels more expected than fruitful, and Debra is only a voice on the phone, the hooks are still in.

Yet Debra wasn’t efficient enough at having total control, which was good for McCurdy. In one of the worst passages of the book, which has the ring of exact truth because it’s quoting an email, Debra tells McCurdy that she’s a slut and that her brothers all agree that they won’t talk to her anymore, and also could she send money to buy a new fridge? If McCurdy didn’t have control over her own money, garnished or not, I’m Glad My Mom Died would either not exist or have turned out very differently indeed.

I’m Glad My Mom Died can be harrowing, but McCurdy has a handle on her material, on the inherent contradictions of knowing that your mother damaged you in multiple ways, being glad that she’s dead, and still missing her. The entire enterprise is believable but also comes across as a fever dream, the subsumption of identity into a crafted persona haunted by multiple horrors.

While not superficial, I’m Glad My Mom Died feels like itbarely scratches the surface. It tells a complete narrative, although it’s obvious that there’s a lot else that happened and the scars run deeper than McCurdy cares to reveal (as is her right). Far from prurient, this is a memoir that feels cathartic for both reader and author alike. That McCurdy has found success at something that she actually wants to do – and has an actual support network around her into the bargain – is perhaps the sweetest outcome of the process.