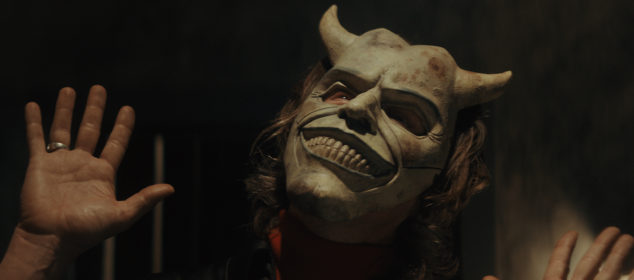

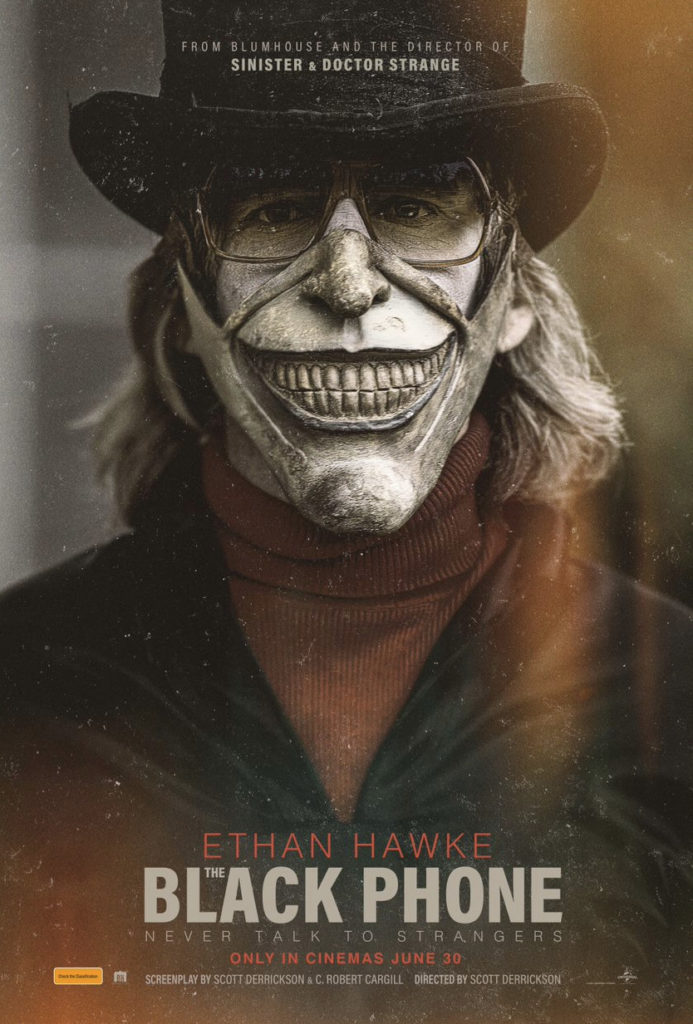

Movie Review: The Black Phone

If you know anything from horror, you’d know that Stephen King has two sons, both of whom are also authors. One of them, Joe Hill, made his name in shorts and comics before revealing his identity. Hill’s 2005 collection 20th Century Ghosts featured a twenty page story called The Black Phone that was, among other things, about a haunted telephone. Twenty pages can fit a lot of detail but, as a film, The Black Phone is proof positive of the power of converting short stories rather than full novels into movies – there’s a lot more room to breathe. Apart from the basic concept, The Black Phone is made up from near whole cloth. There’s so much going for it that it’s difficult to feel bad for Scott Derrickson’s (Doctor Strange) unceremonious ouster from the Marvel Cinematic Universe: some men were meant to not only play, but thrive, in the world of small budget horror.