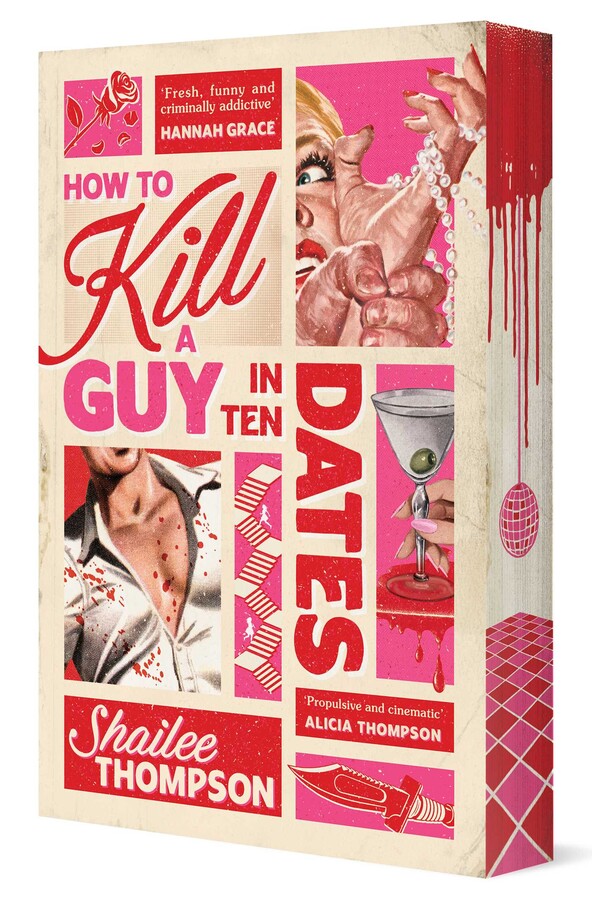

Book Review: How To Kill a Guy in Ten Dates — Shailee Thompson

There are a fair few Australian authors kicking around in genre spaces these days, and the question is always: are they going to set their books in Australia (Jane Harper), their author’s native land like Ireland (Dervla McTiernan & Adrian McKinty), a remote island that doesn’t exist somewhere off Scotland (Laura McCluskey) or … America (Dervla McTiernan & Adrian McKinty)? Brisbane-based Shailee Thompson has decided to go for the United States approach, which is the most logical choice for her combination of those two complementary genres, the rom-com and the slasher film. It really helps to know what you’re in for with How To Kill A Guy in Ten Dates, lest you be surprised that the blood starts spurting at 12%.

Jamie Prescott is writing a dissertation on the intersection between rom-coms and slasher films, and her roommate, Laurie, is an acolyte of documentaries. Having given up on dating apps, Laurie and Jamie go to monthly singles events. On the night that they go to a speed dating event at a labyrinthine club that they attended in their misspent youth (ie five years ago), things go wrong when the lights go out and Jamie’s date’s throat is slit. After that it’s a race for the survivors, shorn of their phones and locked in, to survive the night. But could Jamie maybe find true love on the way, even as the bodies pile up around her?

It feels like at some point over the years it became harder to find a slasher that isn’t self-aware than one that is. This may be even truer of novels, which are not only not films, but often have a stream of consciousness first person narration which means that the lead character can make their commentary on the situation without having to shoehorn it in to dialogue. The book opens with a list of rules for how to survive a slasher, and Jamie refers to them throughout, if only so that other characters can scoff at her.

The problem with having such rigid rules in place is that Thompson is in trouble every time she tries to break one. If you’re even vaguely “up” on the genre then you’ll probably realise a couple of things that Jamie either ignores or discounts, and some of the narrative twists are easily discernible well in advance of their reveals. And then Laurie can say “oh, of course! Just like in [x movie which made hundreds of millions in the nineties, which I have definitely referenced textually]. Why didn’t I see it sooner?” Of course the reader is in a better position to think clearly than Laurie is, but the thing is that Laurie is in a confined space and seems to have a lot of time to think throughout the night — like the multiple instances where she spends ten minutes hiding in silence.

Thompson makes a couple of other uneasy concessions to her second genre, the modern romance novel feeling required to have sexual content no matter how awkwardly inserted it is, so to speak. In one of the moments of quiet contemplation, there is a sexual encounter that is mercifully brief but also you’d have to be there to understand how it’s a sensible thing to do at that juncture (you would also, correctly, guess that this is against Laurie’s rules). It’s not gratuitous, and if you have to do that in this situation, it’s handled sensibly enough. Yet that button didn’t necessarily need to be pressed; sometimes writing within genre is about confounding expectations rather than meeting them.

However, Thompson is right: there are overlaps between Laurie’s genres of choice. It’s not like no one has contemplated the relationship between sex and violence before. Without actors to anchor the ensemble cast to a place and time, it’s difficult to ascribe any characteristics to most of them before they die; Thompson compounds the matter by having separate characters named Drew and Stu, and Laurie frequently accidentally calls Stu by Drew’s name — a problem that doesn’t really resolve itself even after Laurie discovers Drew’s corpse — and the other women beyond Jamie are described as mostly nice except for the very standoffish one (maybe she will become narratively significant?).

The vagueness continues to the club itself, which has a helpful map provided at the front of the book. Apart from it being clearly not up to fire safety code, it’s difficult to get a sense of what its labyrinthine interior is really like. The map doesn’t illuminate much, and it doesn’t seem like there’d be much room to hide from a knife and cleaver wielding maniac in its halls. Yet the ability of a venue to expand and contract as the story demands is thematically appropriate. If ever a scenario crumbles in the face of cold logic, a slasher is the perfect model. No matter the metatextual levels at play, slashers have to respect at least some rules, and here Thompson has made a wise choice.

How to Kill a Guy in Ten Dates is like a slasher itself: some ideas are executed and others escape the page without proper implementation. It’s a better concept than it is an actual novel, but the idea should at least have a market, and Thompson can likely be trusted to write another.

HOW TO KILL A GUY IN TEN DATES | By Shailene Thompson | Atria Australia | 368 Pages

An ARC was provided by Simon & Schuster (Australia) through Netgalley in exchange for review.