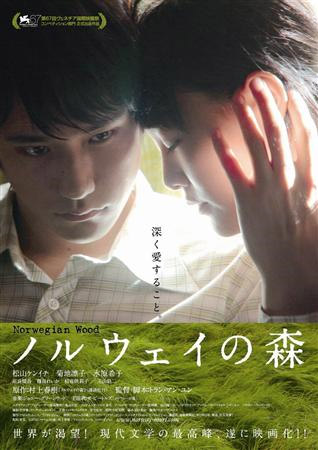

When people see that you’re reading Norwegian Wood, there are two possible responses: “What’s that?” and, of course, “Isn’t it good?”

Ah, the sixties. They were a time. I think, despite my constant exposure to Japanese film, that this is my first time reading Japanese literature. I would like to think that, while this novel is apparently part of a larger canon of sixties student reminiscences, it has been heavily influential in the field of Japan’s romantic drama film industry. That’s precisely what it is: a heavily evocative mood piece about a guy who finds it very difficult to strike any kind of mood at all.

While this is my first foray into reading Japanese literature, it is exceedingly clear that Murakami’s work has been influential in the now common cinematic genre of “sixties student romance”. While a lot of those films have more of the melodrama about them than anything else, they have been touched in some small way by Murakami’s words.

Upon hearing the Beatles tune “Norwegian Wood”, Toru Watanabe remembers his student days and the women he knew, how they affected his life. One in particular, Naoko, may well have been the woman for him … But we know from the first page that it was not to be.

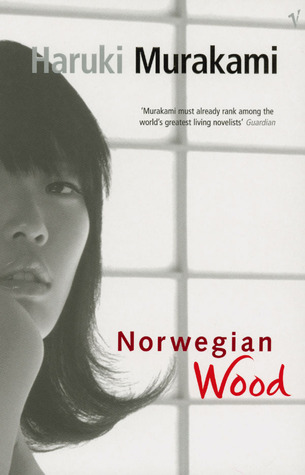

Murakami’s voice, in the translation at least, comes across as strongly evocative of the era it describes. Large swathes of Japan look the same today as they did in the sixties and one could likely do a Norwegian Wood tour of Japan if they so desired, but they don’t need to; Murakami’s is skilled enough to make the reader believe that they’re remembering their own late teens, albeit at a cold remove.

For all his lyricism, Toru is undoubtedly a blank cypher of a character. Not particularly talented in any field, he’s defined by his relationships with the women around him: he is a sponge with no self-esteem, equipped to absorb stories and carry on without an idea of his own self worth. He has no stories of his own to tell people, so he either discusses The Great Gatsby (to minimal success) or his hard-done-by roommate (whose departure he mourns because he now lacks the inspiration to generate new funny stories).

So Toru is at his best when the women in his life are relating their own journeys to him. They have done things, they feel things, that Toru has never allowed himself to engage with. It is with them he is able to relax, but also with them he gets too uptight to manage. He’s not as functioning a member of society as he would have you believe.

Where the book deals sensitively with mental illness, it is merciless on the subject of narcissism. We realise that we don’t have to like Toru because, despite his self-loathing, he is completely oblivious to anything that doesn’t directly involve him. Midori, one of the book’s four women, has a different brand of self-regard that both complements and conflicts with Toru’s own.

Were it not for the constantly looming spectre of suicide, Norwegian Wood could likely represent the sixties student life of just about anywhere. There is a unique Japanese nature to the experience but, despite some very specific situations, it does feel that it contains a universality, albeit one that took 14 years to be dispersed universally. Due to Toru's detached nature it's difficult to have an emotional response to the material; it's like reading through a fine gauze curtain, occasionally taking pause at a particularly impressive passage.

Murakami has ultimately produced an artfully rendered work of slightly broken humanity. Isn’t it good?