“It doesn’t have to be good to be a classic.”

The Joker says this partway through the new animated adaptation of The Killing Joke. Alan Moore’s The Killing Joke, which took the comic world by storm in 1988, has long been controversial for some of its more extreme character decisions. Not everyone agrees that the choices Moore made were wrong and, one way or another, pivotal moments have stuck in the canon almost thirty years later.

Regardless of your stance on The Killing Joke ’88, The Killing Joke 2016 makes it look like a masterpiece. From its insipid original material inserted to pad the running time and provide characterisation that does more harm than help, to its actual adaptation of the source material quite late in the piece, there is very little about The Killing Joke that works.

The first half of The Killing Joke deals with Batgirl chasing down Paris Franz, the presumptive heir to a prestigious Gotham crime family. Paris is a notorious womaniser (read: sexual harasser), and Batman doesn’t approve of Batgirl working the case. This is of course an excuse for Batgirl to work up a head of sexual frustration with Batman and to force her to have talk it through as Barbara Gordon with her gay librarian sidekick – which is approximately as good as it sounds.

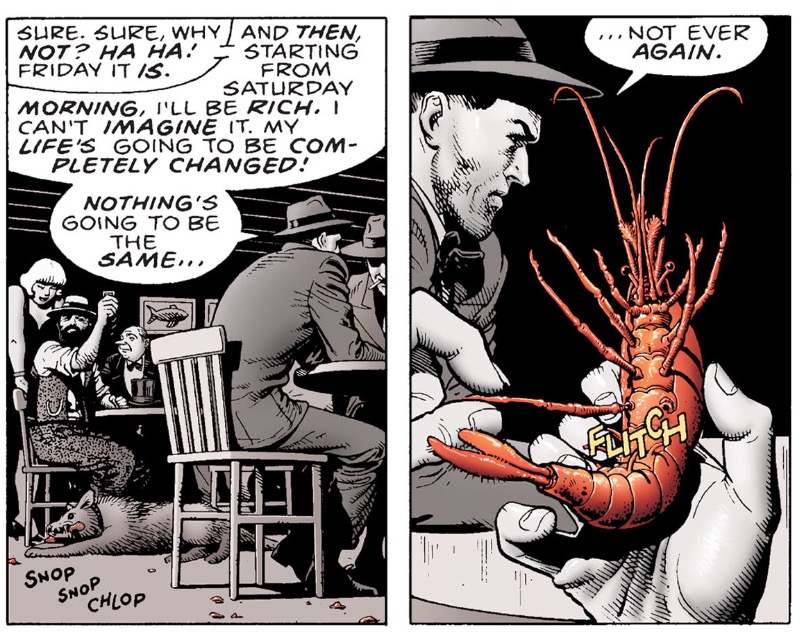

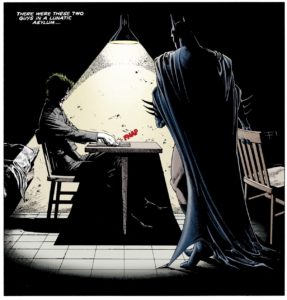

The back end is the actual adaptation of The Killing Joke comic, with the Joker having escaped Arkham and buying an old amusement park for nefarious purposes involving Commissioner Gordon and, of course, Batman himself. Interspersed with the Joker’s plot are unreliable flashbacks to a failed comedian’s sepia toned life …

The Killing Joke ’88 was a 47 page comic, much more about shock than substance – some good lines thrown between Batman and Joker, and some great art, but a weak scheme from the laughing man and a fateful decision that DC has been dealing with the fallout from ever since. The efforts to make the animation longer – still short at 74 minutes – were wasted, as all of the new material is less than optimal.

Barbara Gordon is a pivotal part of The Killing Joke‘s story, but Barbara was never really a character in the original instance. Her utility as a plot device (and how she is used) is one of the biggest sticking points about the property, but Moore’s reliance on the audience’s in-built recognition of Barbara’s place in the Batman universe works better than what we get in the new and “improved” version.

What you’ve got to understand is that Barbara Gordon gets her own story in The Killing Joke 2016, and it’s one about how hung up she is on Batman, not even Bruce Wayne, because Bruce Wayne only gets a single scene in either version of The Killing Joke. Her duality equates to nights as Batgirl wanting to jump on Batman, and days in the library, complaining to her coworker about her complicated feelings for her “yoga instructor” (“and they say the gay scene is complicated”).

Batman is deliberately paternalistic towards Barbara, and if the script had stayed that way, if she had some sort of Electra complex going on that was being gruffly shot down, it might have flown. Instead, we’re supposed to read this as sexual tension. It is understandable that the Bat life might predispose you towards a more unconventional relationship than, say, your camp library aide, but later in the script – the parts drawn from the comic – Barbara mentions having been a child the first time Batman and the Joker clashed. It’s not creepy, but it rings alarm bells.

The Batman of The Killing Joke is an emotionally frozen version of the character, and that is fine, but it also means that he should not take the direction that he does here. It’s one thing that Barbara is not solely to blame for the actions that she takes, but it’s quite another for her to have this reaction to them. To reduce what is supposed to be a complex and headstrong character – personality traits that are by design absent from The Killing Joke ’88 – to a woman who cares less about the crime she fights and more about her semi-requited feelings for a man who dresses up as a bat, is to do her a disservice greater than any perceived or real misdeed perpetrated by Moore in the first place.

The Batman of The Killing Joke is an emotionally frozen version of the character, and that is fine, but it also means that he should not take the direction that he does here. It’s one thing that Barbara is not solely to blame for the actions that she takes, but it’s quite another for her to have this reaction to them. To reduce what is supposed to be a complex and headstrong character – personality traits that are by design absent from The Killing Joke ’88 – to a woman who cares less about the crime she fights and more about her semi-requited feelings for a man who dresses up as a bat, is to do her a disservice greater than any perceived or real misdeed perpetrated by Moore in the first place.

What are we to take from Batgirl removing her costume while Batman stays fully clothed as we pan up to a gargoyle leering down at them? What can reasonably be made of a shot of Barbara jogging, close up on her butt and breasts – her legs and head carefully cropped from the frame so as to be unreadable? Fan service has been around for years, but in some properties it is far more obvious and obnoxious than others. You can’t invite us to be horrified by one form of Barbara’s exploitation while promoting your own unseen camera’s version of the same. It especially doesn’t work in the same title in which Batman gives a lecture about the evils of objectification. The Killing Joke 2016‘s two halves already have no cohesion, but to make each half internally inconsistent is several more layers too far. You can’t strengthen a character by weakening them, and you can’t show one thing and tell another unless you’re a comic book villain yourself. More than before, Barbara Gordon’s role in The Killing Joke 2016 is a tragic misfire.

Where the first and second parts of The Killing Joke clash in particular is the use of technology in the Paris storyline; Batgirl tracks Paris across the city through a series of obnoxious smartphone prompts, which is not in itself a problem, but it becomes one when it grinds against the completely un-updated adaptation of the comic. How can The Killing Joke be set in a modern day Gotham if the pseudo-recollections of the proto-Joker are still situated in a fifties-era tenement apartment and dive bar? Even if you reject the flashbacks out of hand as a concocted sob story that the Joker tells himself – and you probably should, as the whole point of him is that he’s a force of nature rather than a figure to be pinned down and analysed by way of an origin story, plus it’s near certifiable to think that the Joker came about specifically in that way – their incongruously dated nature lend them no credibility whatsoever. To have director Sam Liu take that decision away from the audience is not just insulting, it’s counterproductive.

There is a lot wrong here, and much of it comes down to the use of the Joker. You can’t have a Joker story where the man himself shows up only halfway. Certainly you can get away with that if he’s a spectre looming over the story, or if there’s a build up to him. By having a completely unrelated storyline in order to beef up one character, very little credence is given to the real content of The Killing Joke. Easily the best thing that you can say about the entire project is that Mark Hamill is back as the Joker, and he easily outclasses everything that surrounds him. Good voice work canlift animation out of the doldrums – and The Killing Joke certainly looks like the doldrums -Â and you can almost forgive The Killing Joke in the brief moments that Hamill gets to enliven proceedings. Ultimately, however, you can’t. The parade of grotesquerie that the Joker brings to the table makes The Killing Joke more unpleasant than when it was a by turns dull and unintentionally sexist frippery.

One thing that you can and should demand of a Batman property is that, at the very least, the art is good (don’t tell Frank Miller). For all of The Killing Joke ’88‘s flaws, it is hard to deny that Brian Bolland’s art and colour work (for the 2008 reissue) is exquisite. The aesthetic used for this animation doesn’t read as pale imitation or even shallow parody, but comes across as a lumpen mess. For all of the focus on making Barbara more of a character in her own story, there are frequent instances where shehas either a wonky eye or an almost featureless face. Her most important scene is rendered in a distressingly cartoonish fashion, and its more horrific underpinnings – the ones that arouse the most complaints about the title – are rendered entirely more graphic under the circumstances. Panels are not frames, and a tableau does not translate so well to the screen, but there are definitely times when less is more. The Killing Joke 2016 doubles down on the horror that it has tried to downplay, made it more uncomfortable and unforgivable than it ever was before, and begs that we take it for the apology that it was intended to be.

In taking Bolland’s striking black-and-white with carefully selected highlights away from the flashbacks and render them in sepia with no elements outstanding, you take the grotesquerie of a couple of panels at the fair and stretch them out forever, make them uglier, and set them to music, DC has committed something of a crime against one of their tent poles. The Killing Joke was written in a feverish rush in the first place, but Alan Moore was never so lazy as to depict Batman throwing a dwarf into a pit of spikes. That’s kind of what Batman does not do, and exactly why people had so many problems with Batman v Superman earlier this year. There are things you don’t do in a Batman story and murdering dwarves is one of them. There is not a Batman style guide at hand at the time of writing this piece, but it is a safe bet that it does not endorse Batman inflicted fatalities.

With none of Barbara Gordon’s positive characteristics on display and Batman and the Joker being either absent, watered down or uglied up for the duration, there’s nothing to recommend here. Animation, if it can’t surpass the comics from which it is drawn, should at least supplement them. Producer and Batman animation visionary Bruce Timm – under the influence of a sackful of cash from DC – had hoped to add flesh to something that has been notorious for the entirety of its lifetime. The Killing Joke adds pablum rather than substance and does not even brag Timm’s distinctive aesthetic into the bargain; hideous, pointless and offensive is a triple threat in entirely the wrong direction, and it’s hard to say who has erred the most in the production of The Killing Joke. Are we to blame Timm, Liu or screenwriter Brian Azzarello, who has had respected runs across several DC titles? It’s entirely possible that The Killing Joke was a terrible idea from inception to premiere, but you’d be hard pressed to find someone who will take responsibility for the fact.

The Killing Joke ’88 is a heavily flawed work, but one that boasted excellent art and enduring influence for better and worse. 2016 takes what was viewed as exploitative in the original work and underlines it, runs it through an ugly filter and removes what little beauty, both artistically and thematically, it once had.

2016 is a more progressive place than 1988, and both what comics have to offer and what their readers demand have changed with the times. In taking what was already a throwback, throwing it further back, and pretending that it has somehow evolved, The Killing Joke is more offensive today than it ever was 28 years ago. If you were on the fence about The Killing Joke ’88 before, or if you thought that it was a travesty, don’t watch The Killing Joke 2016. Congratulations, DC: The Killing Joke ’88 is now a goddamn work of art.