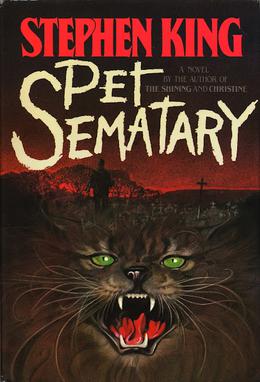

This entry does not contain spoilers for the content of Pet Sematary, but it does address the overall tone of the piece, which, to some people, amounts to the same thing. You have been warned about this 36 year old terror.

Stephen King has that weird sort of luck: terrible things happen to him but they're not as bad as they could have been, or terrible things almost happen to him and they turn into one of his bestsellers, even though he doesn't like the finished product. Though King's personal life is now largely defined by his car accident, back in 1979 young Owen King almost got killed by a truck while the King family lived between a busy road and a Pet Sematary. It did a number on King's psyche, and thus Pet Sematary was born — a book that is too dark and too real for him to enjoy, published largely out of a contractual obligation. Where your standard King novel up to this point (and, admittedly, a few were skipped by this reader to get to Pet Sematary in time for the movie adaptation) offers some degree of hope, regardless of how many terrible events occur between their pages, Pet Sematary is largely a black hole. Abandon all hope ye who inter here.

After taking a job at the University of Maine, Louis Creed moves his family to Ludlow, a town near Bangor, Derry, and not too far from Jerusalem's Lot. The Creeds' new house abuts a busy road out front and, out back, a "Pet Sematary†frequented by the local children. Louis' elderly neighbour Jud Crandall warns him against the dangers of the local trucks, but also tells him more about the local folklore than either of them will end up being comfortable with.

The quaintest element of Pet Sematary is that Louis' initial anxiety is that he has bought a house with a twelve year mortgage. Horror to the people of 1983 is now an impossible dream for the youth of today, to the point that many would take the risk of living next to an unfathomable evil if it meant secure housing. The rest of Pet Sematary checks out, because there's something universal about the fear of death and the ignorance of the idea that there are worse fates.

The opening sentence of Pet Sematary sets the novel up as something that it never becomes: a novel about a man discovering a father figure and learning about the nature of family through the natural progression of life and loss and what have you. It not only takes King a while to properly land the character of Jud but, despite his down-home authenticity, the man never truly seems trustworthy. Some places in King's world are inherently evil, and others are merely populated by evil people; the Micmac Burying Ground is a vampire, and Jud its unwitting familiar. Even if Louis trusts the man implicitly, Pet Sematary is geared so that the reader is naturally suspicious already; whenever Louis has something that he really needs Jud for, they let each other down.

The thread running through Pet Sematary is one about the natural tendency that humans have towards destructively addictive behaviours. Louis himself is reminiscent of a more chill version of Jack Torrance, down to the ambivalence towards his wife and children, but his addiction becomes something entirely more artificial than Jack's own. Where the Overlook had Jack's alcohol dependence to leverage, and a captive audience, the Micmac Burying Ground has to come up with its own draw. The burying ground does not forget, and it does not play fair.

Knowing this, knowing that there's a malevolent force at play, makes the second half of Pet Sematary — the dark half, if you will — that much more tense. Butting against the very notion of free will, something that will come to inform the latter half of The Dark Tower cycle, makes the novel unfold in painful and inevitable slow motion, racing towards its conclusion as it attempts vainly to avoid it. The contrast between Louis plotting his next moves through a mire of molasses and his wife Rachel sensing that she needs desperately to return home without rest or interruption is pulled off in a taut fashion with tension that sings. If ever there was a book that you wanted to rescue the characters from themselves, Pet Sematary is it.

And so Pet Sematary ends abruptly, because there's no 11th hour here. Knowing that he doesn't have to pull anything out of the bag, because he wrote Pet Sematary in the mindset that the bag was empty, King ends it in the most logical fashion he can. This is a novel about the build up, not the pay off, and part two is some of King's more existential work. It's unclear whether it could have really gone any other way: King often uses his child characters as saviours, but that is not an option by design. Ellie's Shine is ignored, and Gage is otherwise indisposed. An addict in a supernatural world may have to acknowledge that the higher power they come to believe in can not restore them to sanity, and Pet Sematary is the way of madness.

Pet Sematary is the sort of novel that speaks to an element of the soul that most would prefer never to have to examine. In many ways it is an expertly crafted novel, playing with the readers' expectations and constantly dashing them, but Pet Sematary is so deeply disquieting that it disturbed even its own author. It's not a surprise that it haunts readers, but whether it satisfies is up to the individual. Pet Sematary stands as technically marvellous, but one can't be blamed for wanting to bury it in the yard and pray that it never comes back.

(Until they go to see the new movie, in cinemas April 4. Stephen King needs your money.)

No Responses