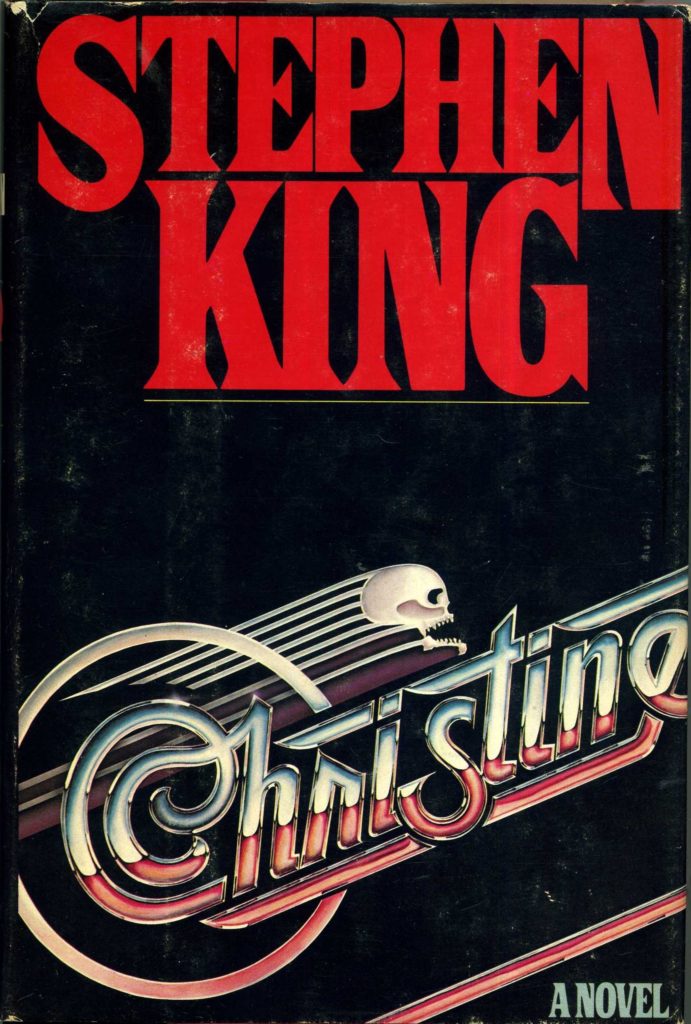

You never forget your friend's first car or their first girlfriend, especially when they're the same entity. Christine, a Stephen King novel released in a banner year for Stephen King novels, is one of those works that earned him the reputation for writing door stops. Christine is an imperfect, fragmented work, more than a little sexist and reactionary, but buried in its six hundred pages is a genuinely sweet paean to friendship lost and the dangers of nostalgia.

King Spoilometer: Christine is best discussed in a more granular fashion, and so this write up will draw attention to late stage revelations as they pertain to the book's overall themes and their presentation.

In the summer of 1978, Dennis Guilder's friendship with designated school "loser†Arnie Cunningham is strained when Arnie buys a clunker of a car: a 1958 Plymouth Fury that he insists be called "Christineâ€. As Christine's bodywork implausibly improves, Arnie's famously bad skin clears up and his good nature becomes remarkably bitter … and when Arnie gets his first girlfriend, Leigh Cabot, is it possible for a car and a girl to hate one another?

More than any other Stephen King novel to that point in time, Christine is a work in parts, and not the way that Hearts in Atlantis, a collection of novellas that coalesced into a single novel, was. Approximately sixty per cent of Christine is in Dennis' first person narration, but the middle forty is third person narrative. It's an act of recalibration for King that could have been better achieved with some judicious editing — this from a Constant Reader who has literally never called for editing of a King work — and it doesn't quite work.

The novel is presented as Dennis writing down the ballad of Christine, including the middle, none of which he was present for, and which is presented in the omniscient third person style King is known for. That Christine is a document inside the world that it describes isn't eye-popping metatextuality, but it does raise questions best left unasked, and undermines the reliability of the narrative. How would Dennis have ever known the thought processes and case histories of people he's barely met, and how does he know how a murder that left no witnesses went down?

It also makes for a jerky — sometimes literally so — story. For part one, "Dennis—Teenage Car Songsâ€, Dennis is more than a bit of a dick, his feelings for his best friend more condescending and contemptuous than actually friendly. Dennis is an openly conservative teenager whose inability to rock boats extends to his disdain for Arnie's "liberal†parents, viewed as feeble-minded and controlling. Regina Cunningham is one of many shrewish nasty mothers that King has committed to the page, but her motivation is entirely lacking — as if, even to herself, she's going through the motions.

Part of what informs Christine's final showdown is Leigh leaving Arnie and taking up with Dennis instead; if she wants to move on to Dennis, that's her business, and no one is beholden to a formerly spotty teen who is now the spiritual prisoner of a misanthropic dead man. It is presented as an immutable rule, this bro code, but realistically if something is not true today — that women are trophies to be fought over by men, with no agency of their own — then it can be true of 1977.

The sexual politics carry over to Christine herself, of course. The car is characterised as a woman, but everything evil that it does can and should be attributed to a man. Christine isn't a "bitchâ€, much as the characters call her one; the car is evil, but that evil is a masculine energy that goes largely unexamined by the characters. They know for a fact that Christine and his prior owner, Roland D. LeBay, are one and the same, but disregard it. Christine was given her own spirit through human sacrifice, but the evil ingredient is LeBay himself, who does double duty as the phantom pilot of the car and Arnie both. The seeds for this are sown poorly, and it is very much as if the first and third parts of Christine do not rhyme at all and no effort was made to connect the dots across multiple drafts. It is a pity because the "facts†of the curious case of Christine, as they stand at the end, come together quite well.

Despite its many problems, it is difficult to hate Christine. Paradoxically, when Dennis returns to narrate the third section, he has softened. He becomes less judgemental of Arnie and more sympathetic about the bizarre situation that his friend is embroiled in. Suddenly it's easy to believe that Dennis and Arnie once shared a loving friendship, and that Dennis misses him. As Arnie loses his soul, Dennis gains a heart — one that should have been there all along.

Although King developed a reputation for not being able to finish a book, anecdotal evidence shows that often he meanders until such time as he can nail down an ending that is, if not perfect, then perfect for the story is telling (and, at the time of Christine, Under the Dome was a good 26 years hence). Christine coalesces, like a car running backward through time to give itself a shine after starting off as a clunker. It is definitely a builder, but it's up to the reader whether they can make it to the genuine rewards that King offers, including a disquieting epilogue that stands with the best of them.

Christine is a long book, and it has glaring flaws in its construction, but it's one of those King books which is able to lift itself out of the doldrums with its moments of shine. Far from his best work, and not exactly needed to be put out in the same year as Pet Sematary, Christine is a book remembered more for the iconography of its title character than its actual content. Despite its inconsistent body work, its spluttering transmission, and more than a few dents in its fender, Christine is roadworthy. It won't get you there fast, and it won't be a smooth journey, but it will get you there.