Yorgos Lanthimos (The Favourite) is an acquired taste, to say the least. Even if he’s presenting a relatively mundane story, there’s a sense of unease hanging around proceedings. Poor Things, however,is not a mundane film. It is a nightmarish and outré work delivered under the dark cover of having a name cast. Whether audiences are suspecting or not is up to them, but they really should have learned their lesson by now: Lanthimos has made a hypnotising tour de force that demands you get with its rhythms or die.

Choose life.

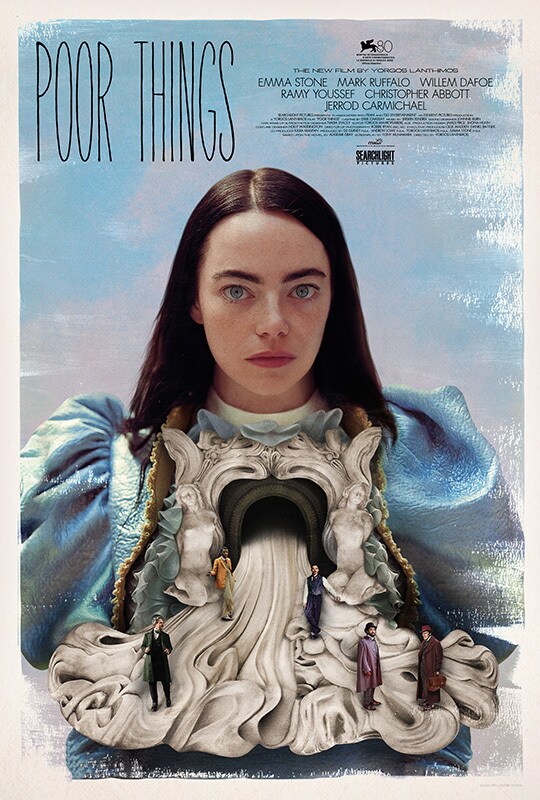

Bella Baxter (Emma Stone, TV’s The Curse) is a woman reborn: the body a suicide with the brain of her unborn baby transplanted into her head. Shortly after Bella’s “father”, surgeon Godwin Baxter (Willem Dafoe, Asteroid City) employs Dr. Max McCandles (Ramy Youssef, TV’s Ramy) to monitor her progress, she meets solicitor and rake Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo, TV’s All The Light We Cannot See), who takes her on a tour of the continent.

Poor Things is designed, from the very beginning, to be offputting. Much of the opening third is shot in black and white, and an alarming amount is done through fish eye or rectilinear lenses. As Bella is unsure of her place in the world, so too are we of our place in the film. Baxter, affectionately referred to by Bella as “God”, offers pronouncements that could be considered unhinged at best.

A shift to full-time colour denotes a shift in the film and Bella’s development. Released from her walled garden, her mind and the picture both are free to open, and Poor Things becomes a big movie in more ways than one. Reality is heightened, humanity is heightened, colours are by turns vibrant and dull; in this way, Lanthimos has fashioned a world, naturalism be damned.

Ruffalo chews more scenery than ever before allowed the man, and loves every second. His physicality and line readings are so pronounced that it would be impossible to miss him. Dafoe, in make up that took four hours to apply and two to remove on a daily basis, is more of a patchwork “monster” than his ward, and is possibly as affable as he’s ever been. There’s gravitas to his statements and a twinkle in his eye as he runs down alternately cheerful anecdotes and objectively terrible personal histories. Youssef marks himself as man of distinction.

Yet Emma Stone is the nucleus around whom the superlative ensemble orbit. Experienced actors have to keep up with her, as Stone is the film’s driving force. Bella is the rare character that an actress is able to build from the ground up, as she is a literal blank slate, and Stone takes every opportunity to stamp herself across the screen. It’s a revelation from a woman who has proven herself several times over, and Bella Baxter is a singular creation, and an excellent figure to build a picture around. There is a lot of sex in the movie, and Stone spends a great deal of it naked, but the male gaze is completely subverted. Almost every action and shot in the film is in service to Bella’s journey of self discovery and Lanthimos is working with Stone rather than against her; this is as star driven a movie as you’re likely to see in a long while.

The script, loosely adapted from Alasdair Gray’s award winning 1992 novel, finds Tony McNamara (TV’s The Great) at his most lyrical. Baxter is poetic, but Bella’s rhythms are so unusual that you are drawn to them, from the simplistic echolalia of her infancy to the complexities of life after she discovers socialism. It’s a pleasure to listen to, but it’s also quite witty. An exchange between Stone and Ruffalo on the streets of Paris is so disarming in its bluntness that it personally puts a cap on an entire segment of the film.

For all of the good feelings that Poor Things ultimately provokes, it’s easy to forget that the tale that it describes contains multiple horrors and ethical dilemmas. Baxter’s justifications for his actions are self-aggrandising at best, and there are hordes of unsympathetic characters clawing at the screen. The story is not without incident or complication, and there are legitimate obstacles to bear or to overcome, but Lanthimos has a genuine warmth for his menagerie and it radiates through the screen.

Poor Things is indeed not for everyone, but it needn’t be. It’s rare that you’ll find such an exquisite corpse as that sewn together by Lanthimos, Stone and her ensemble, and McNamara here. A deeply strange work of art, Poor Things is something akin to a masterwork, its barbed edges the armour for the beating heart at its core.