The Third and Final Act of Australia Week

An excellent film presented by an excellent interviewer, and ably assisted by an excellent actor and director.

To cement the legendariness of this occasion in the eyes of the audience, one member said to Tim Robbins “I’ve been reading about you, and you seem quite liberal and committed to egalitarian causes. Why then do you always play dark bastards?”

Robbins, upon less than a moment’s reflection, responded: “The sanctimonious liberal isn’t a very interesting part.”

There you have it.

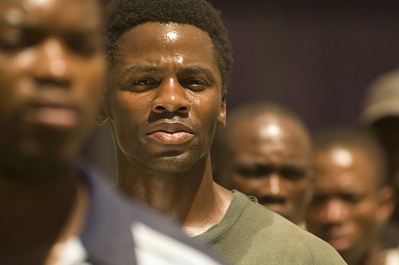

Catch a Fire tells the true story of Patrick Chamusso, played here by Derek Luke, who was arrested and tortured by the South African Special Police Force in relation to a bombing of the power plant where he worked.

Their torture served only to make him exactly what they accused him of being: by their standards a terrorist, by hisa freedom fighter.

Towards the end of Catch a Fire, I realised that my blood was pumping, and not in relation to an excess of sugar. I was wholly invested in what was happening, and the knowledge that these were real people contributed at least partly to that. I know Phillip Noyce only from his work on the The Quiet American, which was amazing, but he worked on taut thrillers to reach the freedom of making such films.

The personal and the explosive meet on such good terms that this is the first movie I’ve been to where the audience could be heard to hiss under their breaths “Yesss!” when something exploded. This is the first film I’ve watched where I’ve thought “the sound is mixed incredibly well”. Battles (and there are only two of them) are tense and confronting as a result.

Patrick seems real, and that is because Derek Luke committed himself to understanding the situation. I did not know the fate of Patrick when I went into the film and, truth thought it may be, I am somewhat hesitant to reveal it here. The suspense created between Patrick and Tim Robbins’ Inspector Nic Vos is delicate and genuine. I was desperate to find out what happened to each of them, and what was real or simply poetic licence. I can only hope that that feeling can transmute itself to a wider audience – one that will realise that this is not as uncomfortable or preachy a film as they might expect.

The interview portion of the night was conducted by Margaret Pomeranz, of At the Movies: one of Australia’s most visible film critics and one of two with whom I take the least issue (the Sydney Morning Herald, for instance, seems to post tangentially related essays instead of reviews … […]).

Noyce and Robbins are, unsurprisingly, quite articulate. They spoke at length of Robbins’ involvement guaranteeing the film’s greenlight; I’d like to imagine that Noyce has a sort of Ray Lawrence effect on actors, but that’s probably wishful thinking on my part.

They are also funny people, and were unafraid to make fun of each other in front of the wider audience. They had no sense of vanity and managed to turn amazingly vapid questions into something of interest. Robbins was even able to give a question that was essentially a mention of the murkiness of Vos’ morality the only response it could ever have received: “thank you”. The ambiguity of Vos’ character was indeed one of the strengths, and Robbins owned his mannerisms. It’s an issue where it’s very easy to take a side, but at least some sympathy can be gleaned for the Afrikaaners who were made to carry out such horrible deeds.

So where does this tie into “Australia Week”, that concept which I sprung on you from the blue? Noyce is an Australian director, but this movie is in no way “about” Australia. Yet I would, on one level, consider Catch a Fire as the ideal future of Australian film. My Best Friend’s Wedding, by Muriel’s Weddings PJ Hogan, is not something that I would consider an Australian film (and not simply because I consider it execrable).

Catch a Fire represents the democracy and international spirit of film. It faced funding from the US in the form of Universal, the UK in the form of Working Title (which was founded by a New Zealander, I might add), and the South African government. The ground crew were solely South African, and Noyce’s normal staff of editors came on board. The film was treated by WETA , and the effects work was done in Melbourne.

We use foreign stars to bankroll our films (Laura Linney and Gabriel Byrne in the brilliant but [subjectively] flawed Jindabyne; Robbins’ wife Susan Sarandon in the unpromoted Irresistible), and consequently each film is given a wider berth.

If we can spread ourselves throughout the world and place our personal (if not cultural) marks on everything that we choose to touch, then Australian Film will not die.