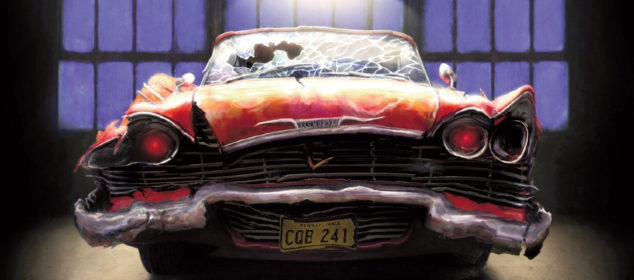

Constant Reader Chronicle: Christine

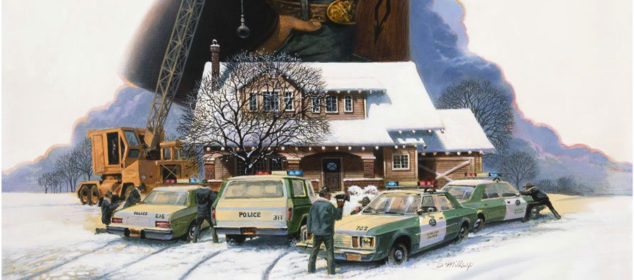

You never forget your friend's first car or their first girlfriend, especially when they're the same entity. Christine, a Stephen King novel released in a banner year for Stephen King novels, is one of those works that earned him the reputation for writing door stops. Christine is an imperfect, fragmented work, more than a little sexist and reactionary, but buried in its six hundred pages is a genuinely sweet paean to friendship lost and the dangers of nostalgia.

King Spoilometer: Christine is best discussed in a more granular fashion, and so this write up will draw attention to late stage revelations as they pertain to the book's overall themes and their presentation.